Potterhanworth Woods

History

In the year 1086 the Domesday Book entry for Potterhanworth noted 150 acres of 'woodland and pasture'. Seven woods were recorded in the parish at the time of the 1776 Enclosure Award and, of these, four remain - Potterhanworth Wood, of some 137 acres and lying to the north of Barff Road, being the largest.

Interestingly, the current total of around 200 acres of woodland in the parish is more than existed at the time of Domesday. Most of the woods in the parish once formed part of the extensive Christ's Hospital Estate, which dated from the early seventeenth century but was almost entirely sold just after the First World War; these woods now belong to a local farming family.

Following a lot of felling before and during the Second World War, Potterhanworth Wood was leased to the Forestry Commission who replanted nearly half the area with oak and conifers, before handing back the management to the owners in the 1980s.

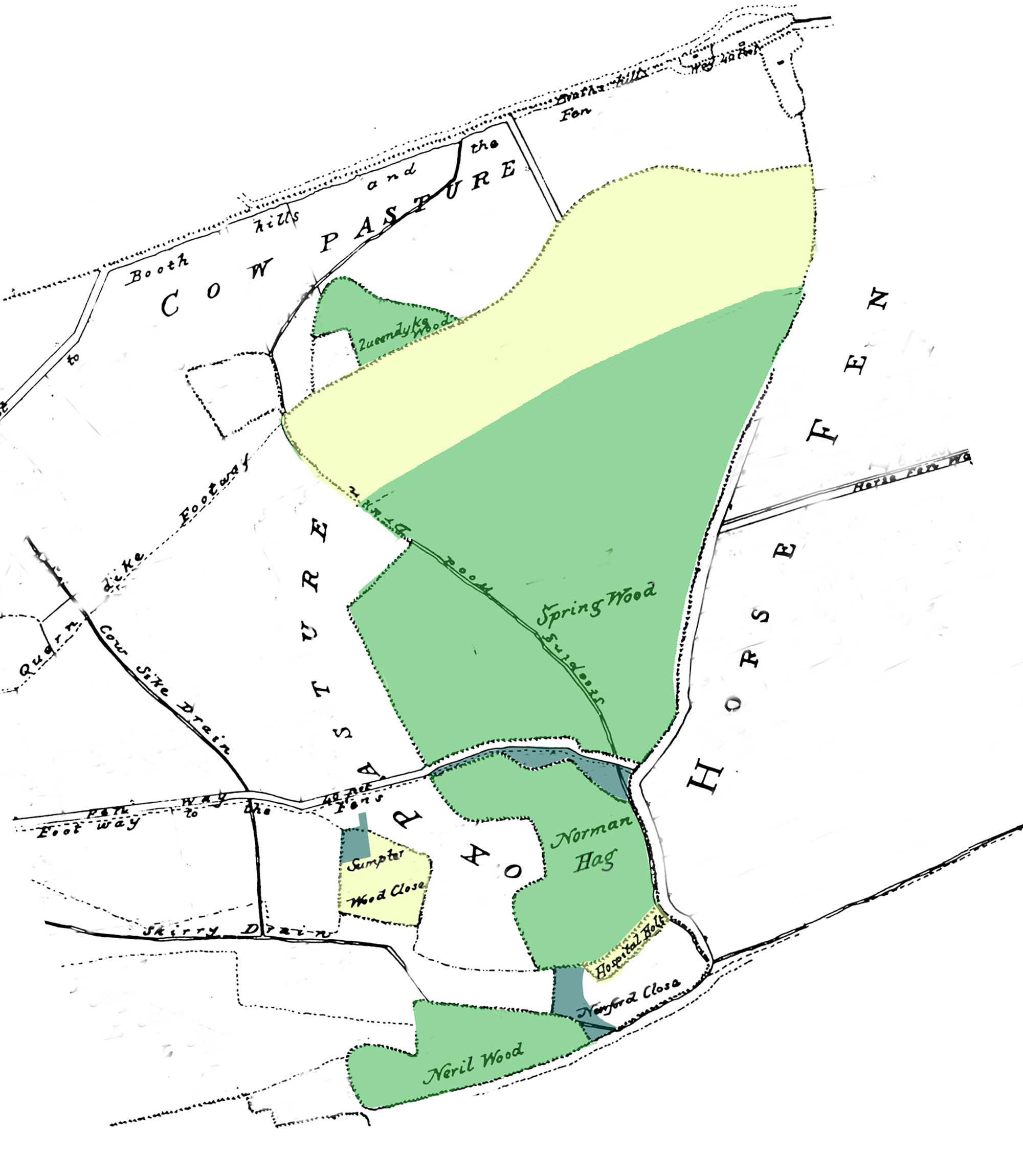

Extract from Potterhanworth Enclosure Map of 1775 showing woodland and adjoining 'open fields'. The woodland which still exists is coloured dark green. Areas coloured yellow are now farmland, but the small areas coloured grey have become new woodland since 1775.

Ancient Woodland

The eastern half of Potterhanworth Wood is classed as 'ancient woodland', defined as woodland which has been in existence since before 1600, and as such is a hugely important and irreplaceable treasure in the countryside. In many cases, such as here, it is likely that this woodland was never replanted and is a vestige of the 'wildwood' of prehistoric times.

Because of its importance, it was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1968. As can be seen, Potterhanworth Wood was named 'Spring Wood' on the 1775 Enclosure Map - an indication of coppicing, a process that involves the regular cutting of the underwood - in this case mostly small-leaved lime and hazel - which then regrows.

The wood produced had many uses in the rural community, including tool handles, gates, hurdles etc, and fuel, and was also used for carving. The lime bark was used to make rope ('bast'), and the flowers for a herbal tea. As coppicing became uncommercial in the twentieth century it fell out of favour in much of the country, but it has been revived in Potterhanworth Wood in recent years.

Above the underwood were quite widely spaced 'standards', mostly oaks, which were allowed to grow to a substantial size before being felled, the resulting timber used for house construction, and for shipbuilding.

Flora and Fauna

The long-term coppicing system has resulted in a rich and varied ecosystem in this SSSI. The predominantly lime tree canopy - even as it closes over again after coppicing - still permits more light to reach the woodland floor than other tree species and the ground flora supports a wide variety of invertebrates, birds and mammals.

The coppicing system creates temporary boundaries between high and low cover, this 'edge effect' being beneficial to many species, also areas of low scrub which again is ideal habitat for particular species.

Other bird species (such as woodcock, chiff chaff, willow and garden warblers) nest on or close to the ground and are particularly vulnerable to disturbance by dogs or humans.

Small-leaved Lime leaves and flowers

Management

Active management of Potterhanworth Wood (and the other adjoining woods in the same ownership) is taking place, all in accordance with a detailed Management Plan agreed with the Forestry Commission, and the management system of the SSSI compartments is further approved by Natural England. Within the SSSI, the north eastern block has been recoppiced over a thirty year period, with most of the produce being used as firewood. Some oak, ash and lime trees have been left as standards, and new oaks planted. Other areas are being managed as 'uneven-aged' forestry, and others are being regularly thinned as 'high forest'.

The other compartments have been managed to make the most of the replanting by the Forestry Commission in the 1950s to 1970s. The area to the west of the main ride was planted with oak and conifers in 1954. Regular thinning has taken place and the conifer 'nurse' trees (which encouraged the oak to grow tall and straight) have mostly gone but the oak are only halfway to their final crop age.

A compartment to the north of the wood had been planted by the Commission with pure conifers but was replanted with oak in 1993 and, following thinning and pruning, is now showing promise. Other areas near the west side of the wood comprised mostly ash but, following the severe effects of ash dieback (the devastating tree fungus first identified in the UK in 2012), have now been replanted with oak and other hardwoods.

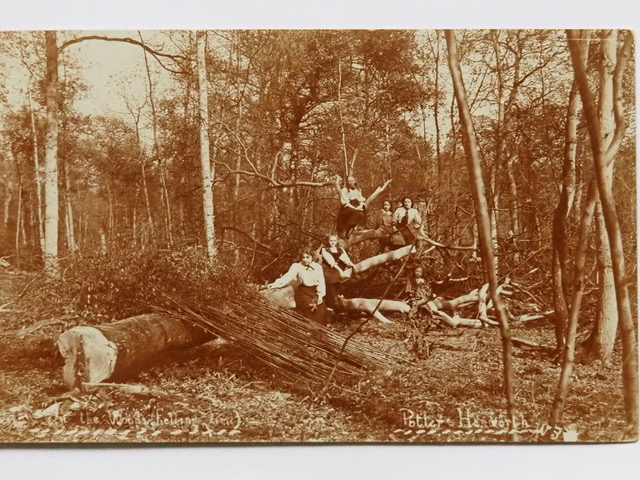

Large oak felled in early 1900s

Pests and Diseases

New tree diseases, such as ash dieback, are constantly appearing in the UK. In recent plantings here up to six different species have been used to spread the risk. But the greatest risk to the woodland - both to the growing of good timber and the enhancement of wildlife habitats - is from deer and grey squirrels. The former, mostly native roe and the introduced muntjac, destroy young trees and clear woods of low scrub and wild flowers, especially bluebells. Grey squirrels can decimate promising hardwood trees at 20-30 years old, destroying the leading shoots and ruining the tree's potential. Control measures for both are vital.

Public Access

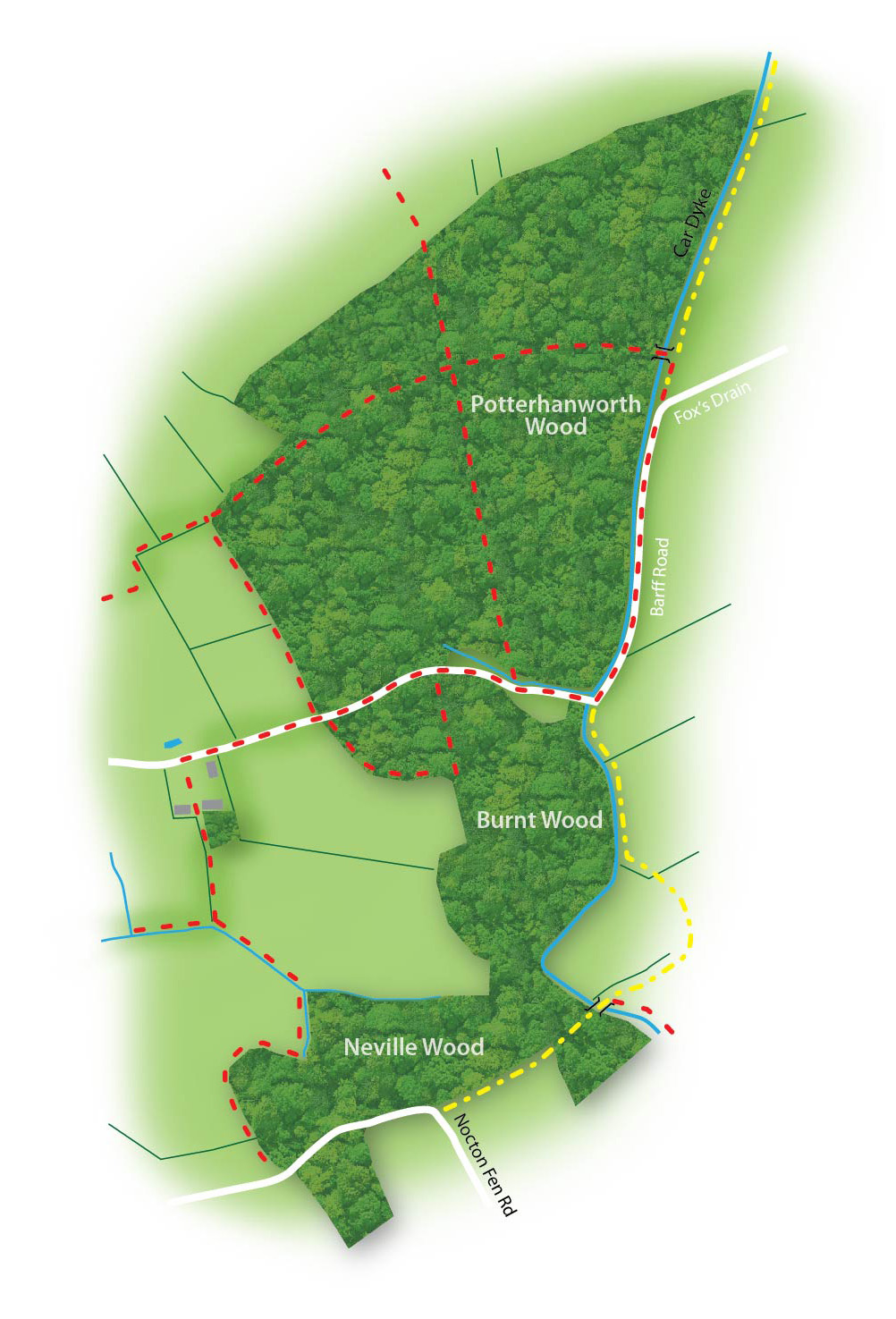

In contrast with other woodland in Lincolnshire which have 'open access', this woodland is privately owned with access only on public rights of way. However, there are a number of well-marked public footpaths through and alongside Potterhanworth Wood, and it is also connected to the village by another public footpath. Walkers are asked to please keep to the public footpaths with their dogs under close control and to take dog excrement - which has a damaging effect on the woodland flora - away with them.

Main ride through Potterhanworth Wood - early 1900s

Climate Change

Woodland is hugely important in the fight against global warming. Acting as a carbon sink it locks up carbon for decades, particularly with actively-managed, vigorously growing trees. The aim in the management of this woodland is as far as possible to produce a final crop of high quality timber which will be used for structural or other uses, rather than as fuel, so the carbon remains locked-up well after the tree's lifetime.

Map showing woodland now existing and public rights of way